Legislative Solutions to California’s Broken Water System Emerge

California’s Bay-Delta system is broken, and everyone knows it. Even groups that rarely agree have independently confirmed that the system is failing the environment, agriculture communities, and urban communities. The challenges facing the Bay-Delta system are due to problems with governance and substance. Thankfully, we are now starting to see important actions that address those challenges.

Congress is taking the lead with a legislative proposal designed to streamline and consolidate decision-making in the Department of Interior. H.R. 3916, The Federally Integrated Species Health Act (FISH Act) would consolidate the management and regulation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) within the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). The bill is designed to address overlapping jurisdictional issues between FWS and the Commerce Department’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) which have led to contradictory policies impacting Westlands and other regions in the Western United States (see FISH Act on page 5). If it becomes law, the FISH Act will prevent two federal agencies from issuing two separate mandates that conflict.

Concurrently, the DOI recently released a reorganization plan designed to improve land and water management for the next 100 years. The specific goals of the reorganization are the following:

- Reduce administrative redundancy and jurisdictional and organizational barriers

- Share agency resources more efficiently

- Devote greater percentage of the agency budget to the core mission

- Improve coordination among federal, state and local agencies

- Facilitate problem-solving

- Make more decisions at the regional level

- Increase responsibility and authority in the field

The DOI demonstrated the need for the reorganization by describing the dysfunction where a dam and streams operate and both salmon and trout exist. In that situation, the DOI explained the salmon are managed by the Department of Commerce through the NMFS and the trout are managed by FWS; water temperatures are managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, unless there’s a hydropower plant, then the Bureau of Reclamation is in charge. Instead of an organized, efficient approach to decisionmaking, the DOI recognized the government, stakeholders, and interested parties are left with a confusing, conflicting process, set up to fail.

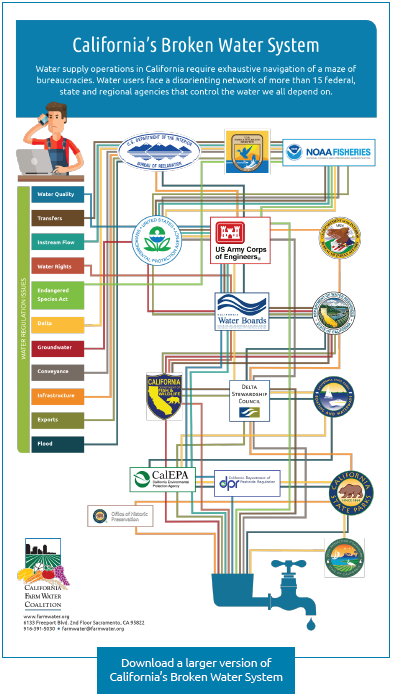

Several years ago, Westlands worked with the California Farm Water Coalition to illustrate the complex and confusing process when attempting to navigate through Bay-Delta governance. See California’s Broken Water System as shown on this page. We will continue to work with our elected and appointed officials and pursue improvements to the Bay-Delta system.

Built to Serve a Variety of Purposes, Water System Struggles to Serve Any

By Johnny Amaral

July 11, 2018

Published in the Fresno Bee

Downstream from majestic Mount Shasta is the Shasta Dam and the reservoir now known as Lake Shasta. According to historical records, dam construction started in 1937, and was such a high priority that when some of the men working on the project went to war, they were replaced by men and women who completed the project in 1945.

Since its completion, Shasta Dam has been enormously successful in providing electrical power, flood control, and water storage. Shasta Lake serves as a recreation area and destination spot for sportsmen, nature lovers and families. The 21-milelong reservoir stores and distributes approximately 20% of the state’s developed water.

South of Shasta Lake, in the San Joaquin Valley, is the San Luis Reservoir, which was completed in 1967. Construction of the San Luis Reservoir was concluded two months ahead of schedule and well under the estimated costs. When the reservoir is full, it holds up to 2 million acre-feet of water supply water, providing water to residents in Los Angeles, San Diego, the Inland Empire, and the Silicon Valley. Water from San Luis Reservoir also irrigates farms throughout the San Joaquin Valley, as intended under the Central Valley Project (CVP) and State Water Project (SWP).

Despite this visionary planning and the enormity of these accomplishments, California’s once world-class water system is not delivering water how or where it was intended because the system is stymied by regulations that defy logic and disregard purpose. Instead of a dynamic process that manages and allocates water resources effectively, the operations of the CVP and SWP are held hostage by inflexible and ineffective regulations. And, despite the water restrictions and the reallocation of water for the expressed purpose of saving fish populations, the decades-long experiment is failing not only fish, but people too.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Government should be capable of accomplishing both important goals of protecting the environment and providing people with an essential element of life. That neither goal is being achieved is unacceptable.

For decades, Shasta Lake fulfilled its purpose. Each year, the reservoir captures millions of acre feet of water, more water during wet years than dry. But after water leaves Shasta Lake, the system is failing to deliver a reliable water supply to communities south of the Shasta that it was intended to serve. Since 1992, the average delivery capability of CVP has steadily declined. Even in years when there is plenty of water, regulations inhibit the delivery of water to communities or to replenish drought-impacted lands.

The 2017 near record rainfall, for example, left water levels in state reservoirs above their historic average, which continued through 2018 (Shasta 102%, Folsom 115%, Trinity 89%, New Melones 128%, and San Luis 95%). But, despite the high level of water storage at the end of the 2017 water year and near average precipitation this year, the Bureau of Reclamation (Bureau) announced that some water districts would receive only a small fraction of their contract supplies. South-of-Delta CVP irrigation contractors, for example, were initially allocated only 20% of their contracted water supply. This allocation was increased to 45% in late May, but this increase came too late for many farmers to efficiently plan their 2018 operations.

Government agencies understandably curtail water supplies during drought. But now, even when water is abundant, CVP operations have shortchanged cities and people, left land starving for water, and jobs in the dust. By their own admission, federal agencies blame restrictions imposed under the Endangered Species Act for limiting operations of the CVP pumping facilities and water deliveries. Yet, despite high demand and abundant water, the paralysis continues. To create a pool of cold water, borne out of concerns for the amount of cold water available for spawning salmon, federal fish agencies have pursued management decisions that declare much of the water off limits, rendering Shasta Lake practically useless. We can protect our native species and move water as historically intended. Gov. Jerry Brown has provided his plan for improving California’s future water infrastructure. And the Water Infrastructure Improvement for the Nation Act (WIIN Act), signed by President Barack Obama in December of 2016, granted federal agencies more flexibility in operating the CVP. Clearly there is bipartisan acknowledgment that the status quo is failing. But more needs to be done if we are to adequately prepare for the future, which will require elected officials to get off their hands and help find a path forward.

The Bureau is currently undertaking a review of existing regulations to develop solutions that will enable communities to have an adequate water supply in the years ahead. That effort will help determine whether California can provide water for the environment and wildlife, and at the same time, maximize water supply to urban and agricultural communities with the water they are contracted to receive.

When California makes these critically necessary changes, we will realize the potential of our water legacy and pay tribute to the contributions of the men and women who built the foundation of our state’s water system many decades ago.

Johnny Amaral is the deputy general manager of external affairs for Westlands Water District, the nation’s largest agricultural water district.

Download: Fish Act: President Obama made a joke, but spoke the truth.